Now my songs of sorrow hear,

Since from thee my griefs do grow

Whom alive I prized so dear:

The more my joy, the more my woe.

John Coprario

Funeral Teares (1606)

Von allem, was geschieht, ist eines nur,

wovor der Götter Lächeln nicht besteht: der Abschied.

(Of all the things that can happen,

only one fails to make the Gods smile: saying farewell.)

Petr Kien

Der Kaiser von Atlantis (1944)

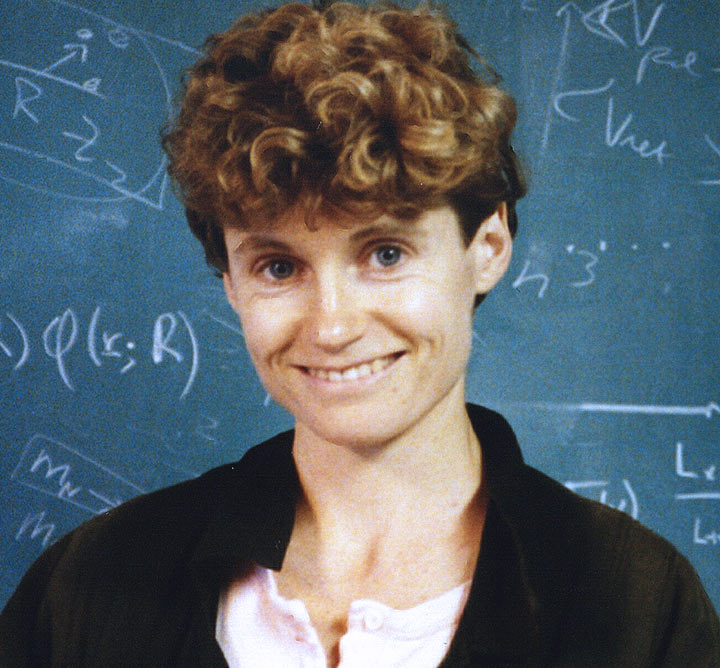

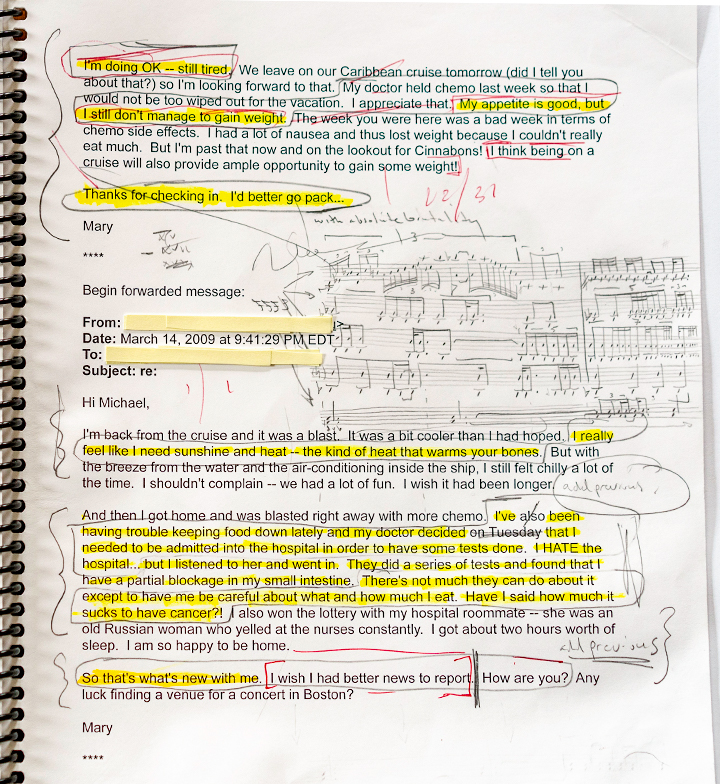

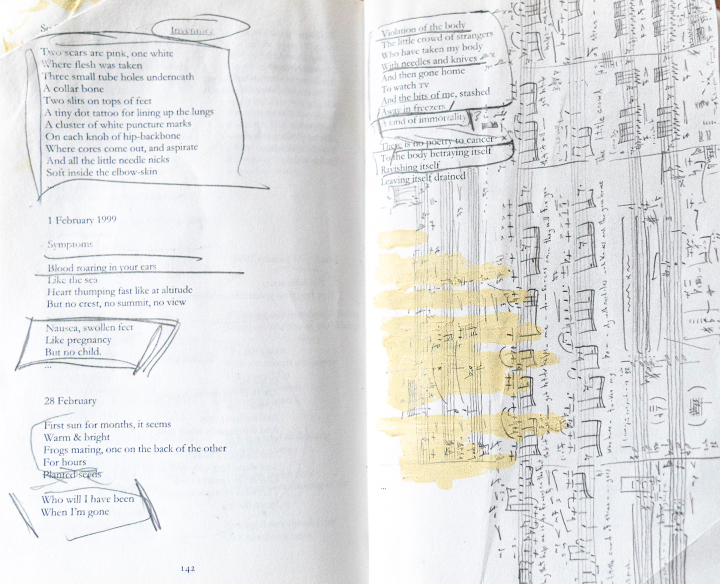

In Illness as Metaphor Susan Sontag wrote, “Cancer is a rare and still scandalous subject for poetry; and it seems unimaginable to aestheticize the disease.” Michael Hersch confronted that dilemma in his monodrama On the Threshold of Winter (2012) setting texts by the Romanian poet Marin Sorescu, who died from cancer in 1996. Hersch addressed the topic again in I hope we get a chance to visit soon, conceived as a companion piece, that reflects upon the loss of a close friend, Mary Harris O’Reilly (1964-2009) to ovarian cancer. If Sorescu’s verse hovered “between reality and a fantastical, nightmarish place,” Hersch has written, the directness of the text in I hope we get a chance to visit soon “allows little room for escapism.” The principal texts of the work are drawn from O’Reilly’s correspondence with Hersch (Soprano I) as well as fragments of poetry (Soprano II) by Rebecca Elson (1960-1999) who likewise succumbed to cancer. Whereas O’Reilly’s letters have the unembellished immediacy of confidences with a trusted friend, Elson’s verse approaches cancer through imagery and metaphors.

And yet, notes Hersch, “Elson’s poetry seems to articulate in direct terms what much of O’Reilly’s thoughts refuse to openly acknowledge.” This tension differentiates the two soloists, who are often heard separately, in alternation, or in counterpoint, but only toward the end more directly in tandem as if O’Reilly and Elson, in moments of extremity, are intersecting unawares. Over the course of sixteen discrete movements, their words, variously spoken, intoned, whispered, or sung, sometimes impassively and in mid register, sometimes with searing intensity in the highest reaches, trace the same story, an experiential arc that moves from the terror of diagnosis to the harsh indignities of treatment, and the inevitability of death.

As a prelude to these texts Hersch introduces a third source, poetry by Christopher Middleton (1926-2015), someone with whom Hersch often worked. This first and longest section is a work in its own right – a fascinating adaptation and elaboration of an earlier piece for voice, violin, and cello, …das Rückrat berstend (2017), in which Hersch set fragments of Middleton’s verse in German translation. Here, spoken in English and German, the succession of images – from agitation (“rushing,” “onhurled”/”rasen,” “vorangeschleudert”) to violence (“exploding,” “tear off”/ “berstend,” “abreissen”) and on toward oblivion (“absence,” “abyss”/“Verlassenheit,” “Abgrund”) – anticipates both the trajectory of the experiences of O’Reilly and Elson, as well as the differentiation between the soloists in the visceral immediacy of English and the subtle remove of German translation. Together, in rhythmic declamation, sometimes closely linked, at others slightly out of synch, they navigate their way through and around an instrumental landscape that is distinctly sculptural, physical: jagged objects, glaring light, immovable clusters that loom up and recede. In dramatic terms, this preliminary movement is akin to the allegorical prologue to a mystery play or a baroque opera.

The following 15 sections are approached differently, less “composed,” largely because the disparate narrative and poetic texts are more open-ended: a succession of tableaux, each grappling anew with the incomprehensible. Rhythmic speech and flatly intoned recitative, often unaccompanied, also tend to disrupt the musical flow. Moreover, each of the sections, the first few quite short, then increasing in length, is quite individual in scoring and musical character (though occasional text repetitions are accompanied by varied musical recall), veering from soft, meticulously notated micro-tonal inflections to bold gestures and drastic effects.

Hersch’s approach to this material feels more ambiguous. In selecting and arranging his texts he has, of course, shaped a narrative. On the other hand, he has described the work as an elegy, a work of lamentation and remembrance. If this is a deeply personal work, intensified by the fact that he himself is a cancer survivor, it is also a work in which he takes his distance, as if still grappling with the “grinding feeling of unresolvedness” that has haunted him since O’Reilly’s death. It is the empathy of the observer, helpless to intervene. We learn nothing of his side of the correspondence, but his music provides a seismographic response to shifting psychic states without presuming to offer concrete illustration. In general, the instruments punctuate rather than accompany the two soloists, but there are a number of extended instrumental passages, at the outset or conclusion of individual sections, or in interludes that suggest more generalized evocations of fear, slashing outbursts panic, anguish, and pain, hushed wrenching sonorities of wan hope, stoic resolve, and the dull weight of resignation. The third and shortest section is in fact wholly instrumental, an explosion of terror following the matter-of-fact spoken revelation of O’Reilly’s diagnosis. Yet for all its expressive urgency, this is music of restraint. Hersch’s meticulous performance instructions warn against excessive vibrato, place stress on rhythmic precision, and insist on a measured pace and on giving rests their full value. The singers, in turn, are urged to speak simply, naturally, and with “sober deliberateness.” The result is a work that is at once unsparing and profoundly compassionate. And it is in its emotional reserve that its compassion is most moving.

It is a curious quality of this music that its violent eruptions and knotted dissonances serve to heighten our awareness of individual gestures such as the sudden appearance of a consonant interval, a single note in the clarinet, an insistent interjection by the saxophone, or the jangle of plucked or brushed piano strings. Most striking is a haunting piano solo that first appears at the outset of movement six and has an independent identity quite unlike anything else in the piece: calm, introspective, and strangely consoling, but a thing apart, something ancient, or, more specifically, out of time. It has the feel of a late Renaissance Déploration, a musical world that seems to lurk beneath the surface in other works by Hersch, as well. It is an episode of detached serenity amid savage interjections. There are subtle allusions to this passage – a pitch, a sonority – in various sections, but its full return in section 12, first in the piano, then in the winds, marks a dramatic turning point. The voices – speaking – appear only at the end of this section: Soprano I, almost guttural, inhuman, “…it’s dark, cold and snowy outside”; Soprano II, in a whisper, “Sometimes as an antidote/To fear of death,/I eat the stars …”

It is the beginning of a slow descent. In section 13 the pace is deliberate, and the texts speak bluntly of the ravaging effects of the disease. “Far from revealing anything spiritual,” Sontag has written, cancer “reveals that the body is, all too woefully, just the body.” Notable at this point is the increasing frequency of overlap in the vocal lines as they move together toward stasis. In the following movement (tr 14), the longest in the main body of the piece, the voices progress from monotone and speaking toward the last great vocal (and instrumental) paroxysm before sinking back into a monotone. Section 15 contains striking moments of luminous vocal concord, an arresting minor third on C# and E, a hovering, enigmatic refrain. I hope we get a chance to visit soon concludes as it began, with unaccompanied speech, energies now spent. Just before the end, over gently sustained sonorities:

“…it’s kind of hard not to be frightened …”

“Boiling with light,

Towards the sharp.

night ...”